This is an entry that I posted a couple of days ago but, in light of the new promo, I have something to add. The promo’s music, Jim Morrison’s “The End,” is another nod to Apocalypse Now in which the song serves as a compelling backdrop for the film’s most significant scene (no spoilers here but if you want to view the scene, a very graphic one containing explicit language, mind you, click to see a youtube clip)

Here are a couple of stanzas that are interesting when interpreted through a “Lost lens” and the lyrics in their entirety are provided at the bottom of this posting.

“This is the end, beautiful friend/This is the end, my only friend/The end of our elaborate plans/The end of everything that stands/The end

The killer awoke before dawn/He put his boots on/He took a face from the ancient gallery/And he walked on down the hall

He went into the room where his sister lived/And then he paid a visit to his brother/And then he walked on down the hall/And he came to a door/And he looked inside/Father?/Yes son/I want to kill you/Mother, I want to………….”

–Jim Morrison

And now begins my original “Apocalyptic Heart of Darkness” bit:

“The wilderness had found him out early, and had taken on him a terrible vengeance for the fantastic

invasion. I think it had whispered to him things about himself which he did not know, things of which he had no conception till he took counsel with this great solitude–and the whisper had proved irresistibly fascinating. It echoed loudly within him because he was hollow at the core” –Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

Young Locke's prophetic rendering of the Smoke Monster

The corruptibility of the human soul is a central theme of both Heart of Darkness and Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 movie, Apocalypse Now. The latter is a loose interpretation of Conrad’s novella but set in a very different time and place. Both stories prefigure Lost’s concern with the nature of evil and the tension between wilderness and civilization, isolation and community.

So is Lost an updated interpretation of Heart of Darkness emerging from yet another medium and genre, the television drama? Probably not. If we’ve learned anything about Lost’s vast array of literary and pop culture references it’s that, taken individually, they act like red herrings, leading us down narrow, winding trails to nowhere; yet they always provide a deeper understanding of the show’s themes and characters. Taken together they help to expand the meaning of the show, which is sometimes a great relief when meaning within the text seems a little thin.

But I find it particularly interesting that a recent promotional trailer featured the famous lines of Conrad’s novel, probably even more familiar to modern viewers as the dialogue from Apocalypse Now: “The horror, the horror.” In fact, the entire promo was centered around this and another line from Heart of Darkness. The short clip shows John Locke, the smoke monster, marching towards some of Widmore’s men with a menacing expression on his face while the words on the bottom of the screen read “His soul had gone mad. Being alone in the wilderness.” Here is the full passage from the novel: “But his soul was mad. Being alone in the wilderness, it had looked within itself, and, by heavens! I tell you, it had gone mad. I had–for my sins, I suppose–to go through the ordeal of looking into it myself. No eloquence would have been so withering to one’s belief in mankind as his final burst of sincerity. He struggled with himself, too. I saw it,–I heard it. I saw the inconceivable mystery of a soul that knew no restraint, no faith, and no fear, yet struggling blindly with itself.”

Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now

An excerpt of dialogue from the film Apocalypse Now shows an even more explicit study of the struggle between good and evil. Before General Corman sends Willard on his mission to find Colonel Kurtz, a man engaging in horrendous acts of violence against the native people, he warns him of the limits of the human spirit: ” There’s conflict in every human heart between the rational and the irrational, between good and evil. The good does not always triumph. Sometimes the dark side overcomes what Lincoln called the better angels of our nature. Every man has got a breaking point….Walter Kurtz has reached his. And very obviously he has gone insane.”

This is one way to look at evil—as insanity, beyond the pale of anything rational. Is this what the Smoke Monster embodies? Pure madness? For certain, we know Claire has been left in the wilderness and reached her breaking point. Sayid was pushed over the edge by his own actions and the inability to forgive himself. And Ben, the original bad guy, has always exhibited signs of mental instability. Perhaps the Smoke Monster’s plan works this way: the more “mad souls” that he recruits, the stronger he becomes. The apocalypse will come to pass one “infected” spirit at a time.

“The End” by Jim Morrison

(Featured in the 1979 film Apocalypse Now)

This is the end, beautiful friend

This is the end, my only friend

The end of our elaborate plans

The end of ev’rything that stands

The end

No safety or surprise

The end

I’ll never look into your eyes again

Can you picture what will be

So limitless and free

Desperately in need of

some strangers hand

In a desperate land

Lost in a Roman wilderness of pain

And all the children are insane

All the children are insane

Waiting for the summer rain

There’s danger on the edge of town

Ride the king’s highway

Weird scenes inside the goldmine

Ride the highway West baby

Ride the snake

Ride the snake

To the lake

To the lake

The ancient lake baby

The snake is long

Seven miles

Ride the snake

He’s old

And his skin is cold

The west is the best

The west is the best

Get here and we’ll do the rest

The blue bus is calling us

The blue bus is calling us

Driver, where you taking us?

The killer awoke before dawn

He put his boots on

He took a face from the ancient gallery

And he walked on down the hall

He went into the room where his sister lived

And then he paid a visit to his brother

And then he walked on down the hall

And he came to a door

And he looked inside

Father?

Yes son

I want to kill you

Mother, I want to………….

Come on, baby, take a chance with us

Come on, baby, take a chance with us

Come on, baby, take a chance with us

And meet me at the back of the blue bus

This is the end, beautiful friend

This is the end, my only friend

The end

It hurts to set you free

But you’ll never follow me

The end of laughter and soft lies

The end of nights we tried to die

This is the end

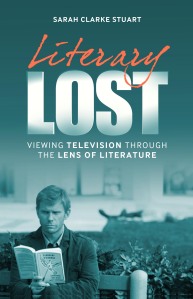

Announcing the official publication of Literary Lost: Viewing Television through the Lens of Literature by Sarah Clarke Stuart.

Announcing the official publication of Literary Lost: Viewing Television through the Lens of Literature by Sarah Clarke Stuart.